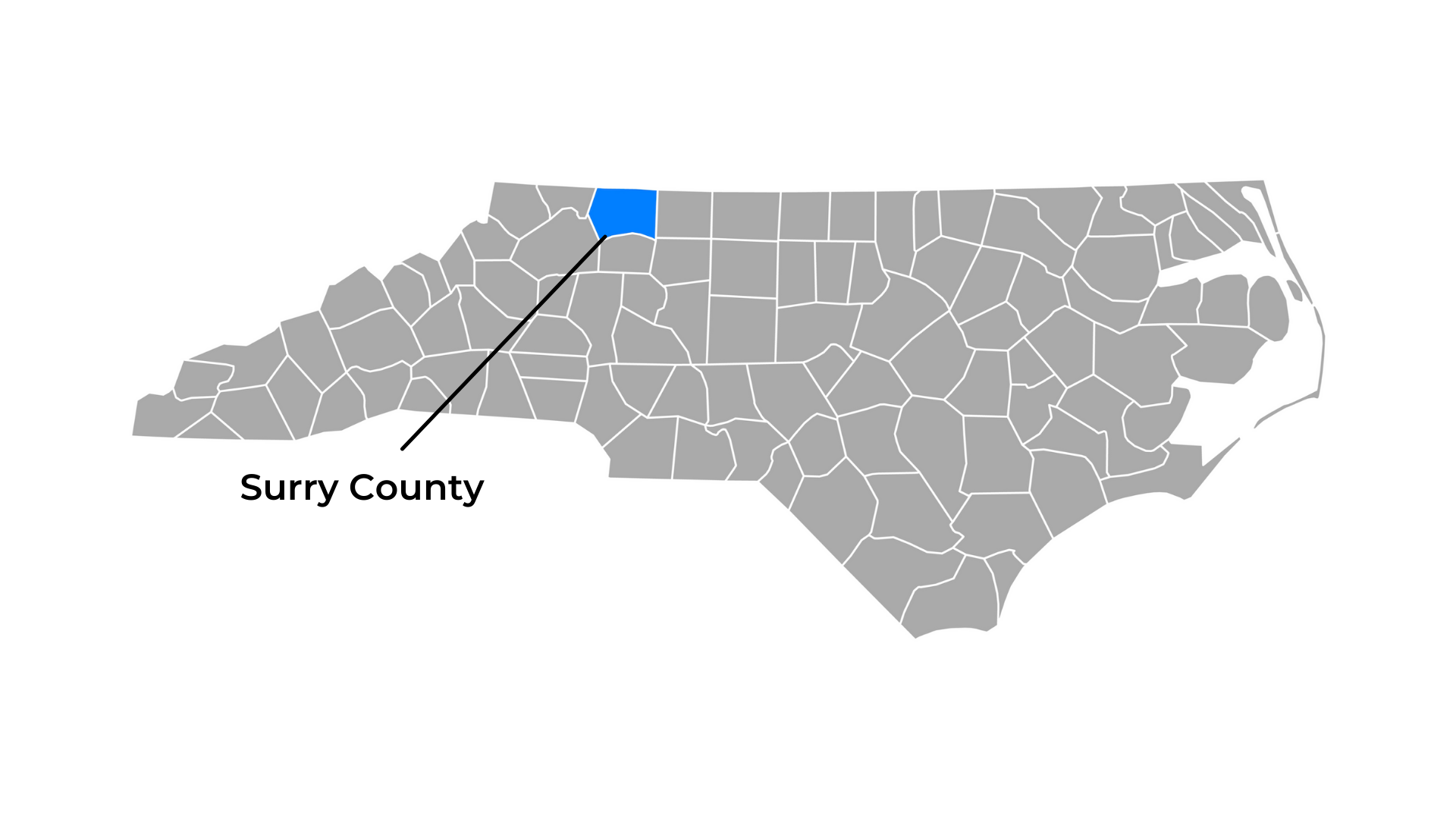

These are hard times for many folks in Surry County, a part of the state struggling to overcome the loss of textile, furniture and tobacco jobs. Nearly one in six people live below the poverty line, well above the national average of 12.3 percent.

In 2017, the college surveyed first-year students about potential obstacles to focusing on their coursework. The responses — centered on basic necessities like food, laundry detergent and hygiene supplies — prompted Kennette Thomas to take action.

Today, the project she launched has an official name – the Little Free Pantry of Surry Community College – and a team of supporters who keep it stocked with non-perishable foods (ready-to-eat and take home) and things like diapers, shampoo and tooth brushes. It has become a vital community resource, particularly since the pandemic upended our lives.

“Sometimes, it is nearly cleared out over a weekend or within one week,” Kennette said. “The need for this ministry has only grown.”

The Foundation’s Reynolds Ministry Fund served as a sustaining partner. Grants over two years helped replenish supplies at a time when grocery prices are sharply increasing.

For Kennette, who teaches English and religion at the college’s main campus in Dobson, the pantry was a way to bridge her two vocations. She’s also an ordained United Methodist deacon with a passion for social justice.

The ministry has taken on a life beyond what Kennette imagined. When COVID-19 arrived, the pantry became a pick-up spot for facemasks with encouraging quotes, thanks to a laity-clergy partnership with Central UMC of Mt. Airy, where Kennette serves in a part-time role. Wipes and hand sanitizer also were added.

The pantry stands along the main drive of campus but not in a high-traffic area. That was intentional, Kennette says, because students and members of the community often have a stigma attached to asking for assistance.

A movement to address food insecurity

This is what Jessica McClard had in mind when she launched the grassroots mini-pantry movement in May 2016 in Fayetteville, Ark. Jessica planted a wooden box on a post and stocked it with food and household items accessible to everyone all the time, no questions asked.

Jessica hoped her spin on the Little Free Library concept would raise awareness of food insecurity while creating a space to meet neighborhood food needs. Within a few months, the movement was global, according to LittleFreePantry.org, a site that chronicles the history and shows images of pantries around the globe.

Many bricks-and-mortar food pantries require an application. They fall under the category of service providers; those who use them are “clients.” Little free pantries dissolve that boundary, albeit on a smaller scale. Whether giving or taking, everyone approaches the same way, easing the shame that accompanies need.

And in Surry County, there is considerable need. The loss of major employers coincided with the arrival of the opioid crisis, which has devastated many families. At the end of August, 31 people had died from an overdose in Surry County in 2021, equaling the number who died in all of 2020, according to the county’s Substance Abuse Recovery Office. Statewide, there were 3,132 fatal overdoses in 2020, a 16 percent increase from 2019.

Compared to other counties, Surry County has an unusually high number of residents working in production (1.75 times higher than expected), construction and extraction (1.48 times), and farming, fishing and forestry occupations (1.46 times).

An outpouring of gratitude

Kennette said students and faculty members walk up while she’s stocking the pantry to thank her for what she’s doing. Colleagues share stories of watching students get out of the car for school, reach into the pantry and hand younger siblings cereal bars and Pop-tarts.

It’s even become part of the curriculum. During a discussion on social responsibility practices, students in an Introduction to Business course considered how they could give back as individuals and become social change agents in their own communities.

Donations poured in, and several students contributed more than 20 items.

On the shelves next to cereal boxes and soup cans, there is information about local resources, handmade prayer squares (part of Central UMC’s prayer shawl ministry) and seasonal items such as hats, scarves and mittens.

Another blessing occurred recently – this time due to an unfortunate circumstance. The college will close its Medical Assisting Program in the spring, and the discontinuation will mean the end of a club for students in the program. A faculty adviser shared the club’s remaining balance of $4,000 to go toward supplies for the pantry.

This contribution, coupled with ongoing support from Central UMC, will help to sustain the ministry well into the future.

Dr. Dawn Hawks, a business instructor, and Kennette Thomas stand behind donations that students made to the Little Free Pantry.

For Cross Connection, new name reflects big plans for growth

"The heart of Cross Connection is the same," the executive director said. "We’re still rooted in Christ—and growing into a fuller vision of the Church."

A pastor and his trumpet bring new energy to High Point church

Jazz is a regular part of worship at Memorial UMC in High Point, where Rev. Darryl Donnell brings a relatable style to preaching the Word.

An Asheville church seeks to ‘restore dignity’ in a time of fear

An Asheville congregation has befriended Spanish-speaking neighbors through a mobile food market, block parties and Know Your Rights events.